Psychological Symptoms in People Presenting for Weight Management

Cheryl B L Loh,1MBBS, M Med (Psychiatry), Yiong Huak Chan,2BMaths (Hons), PGDip (AppStats), PhD

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Elevated levels of psychopathology have been described in various groups of obese patients. This study aimed to describe the presence of depressive and binge eating symptoms in patients presented for clinical weight management at a general hospital in Singapore, as well as their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Correlations between these symptoms and other demographic and clinical variables were also sought. Materials and Methods: Patients presented at a clinical weight management programme were asked to complete the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Binge Eating Scale (BES) and the Short Form-36 (SF-36). Clinical and demographic data were also collected. Results: Of the group, 17.1% reported moderate or severe binge eating symptoms and 9.7% reported moderate or severe depressive symptoms. HRQOL, mostly in physical health domains, was lower in this sample compared to local norms. Within the group, binge eating and depressive symptoms, but not increasing obesity, predicted poorer HRQOL. Conclusions: Psychological symptoms are signifi cantly present in patients presented for clinical weight management and these contribute to poorer quality of life. Addressing these symptoms will improve the overall well beings of these patients and the total benefi ts gained will exceed the benefi ts of weight loss per se.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple factors contribute to the genesis and maintenance of obesity which is a difficult condition to treat and weight loss is often not maintained. The psychological problems found in obese patients have recently received increasing attention. Many recent studies have found increased levels of depression, anxiety and binge eating disorder among patients seeking clinical weight management. One study conducted on bariatric surgery candidates found that they had almost 4 times elevated rate of major depression (19% vs 5%) compared with non-obese controls.1

The first part of our study looks at the prevalence of depressive and binge eating symptoms in a Singaporean clinical population presented for weight management.

In a society where trim figures are highly prized, obesity can sometimes lead to disappointments when finding jobs and making friends. Also, depressive illnesses are often characterised by changes in appetite, low energy levels and lack of interest in activities – all of which might contribute to weight gain. Together with a sense of low self-efficacy, these symptoms hinder weight reduction, which requires diet control and increased participation in exercise.

Binge eating is studied because it is often associated with depressed mood and is of particular interest in post-bariatric surgery patients who need to control their eating habits. Binge eating is defined as recurrent episodes of eating a large amount of food rapidly and having a sense of loss of control over eating. Eating, in this case, is usually not related to hunger and patients will eat until uncomfortably full. It is associated with mental preoccupations with eating and guilt about over-eating. Binge eating has been studied both as a symptom itself and as a mediating factor between depressed mood and obesity. A study of obese subjects found a prevalence of 51% for major depressive disorder among those suffering from binge eating versus 14% in those without.2 In addition, the current study investigates the link between being depressive and binge eating symptoms in our patients.

The direction of causality between mood and obesity is far from conclusively known. Bejerkeset et al3 found that the baseline body mass index (BMI) was associated with depression in a cohort followed-up over a period of 20 years, while another study (Hasler et al4) found that the baseline depression was associated with later obesity. Outcome studies from weight loss programmes and bariatric surgery show varying effects on measures of psychological symptoms.5,6 We cannot assume that the increased psychopathology found in patients presenting for weight management will disappear with weight reduction. Also, if the psychological symptoms contributed signifi cantly to obesity, failure to treat them would result in recurrence of weight gain.

The second part of our study looks at the parts obesity and psychological symptoms play in a measure of overall quality of life. Obesity has previously been found to be associated with lower quality of life in several physical domains.7 We first measured quality of life using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) and then sought to find its associations with the levels of obesity or psychopathology. This then suggests whether it is obesity per se that impairs quality of life, or the presence of psychological symptoms that causes distress and lowers perceived quality of life. This will also help us to understand the importance of psychological intervention for those in weight management programmes and are having concurrent psychological symptoms.

Materials and Methods

All new cases aged between 21 and 65 years old presented for the first time at the weight management programme at Changi General Hospital between October 2006 and October 2007 were invited to participate. Basic patient data such as age, gender, race, history of medical and psychiatric illness and BMI were gathered from the case sheet review.

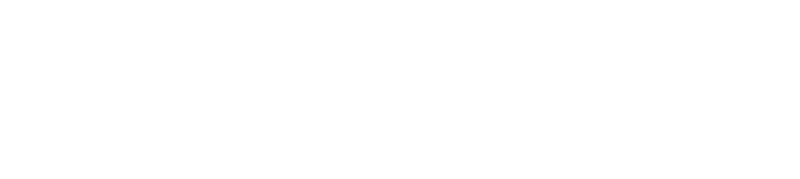

The patients were then asked to fill in a one-time selfreported questionnaire consisting of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Binge Eating Scale (BES), Short Form-36 (SF-36) and Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scale. BDI is a widely used measure of depressive symptoms whereas BES is a measure of binge eating habits and cognitions. Neither BDI nor BES are diagnostic tests though scoring categories for delineating minimal, mild, moderate and severe symptoms have been established. However, both are easily self-administered, and are often used in studies of obesity and mood and have been extensively tested for validity and reliability although not in local populations. The scores and categories are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

SF-36 is the most commonly used generic instrument for medical outcomes. Local norms were published in 20028 and the scores are broken down into 8 domains, namely: (i) physical functioning, (ii) role limitation due to physical problems, (iii) bodily pain, (iv) general health, (v) vitality, (vi) social functioning, (vii) role limitation due to emotional problems and (viii) emotional well-being. Raw scores are transformed to a 0 to 100 scale where 0 is the lowest possible score which usually denotes impairment and defects and 100 is the highest score obtainable which denotes no limitations or problems in that area. The scores are used in comparison with the norms for a given population. In this study, we compared the obese patients (our study cohort) with the general Singapore population.

Data were analysed using Statistical package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0. Differences for continuous variables between groups were tested using t-test when normality and homogeneity assumptions were satisfi ed; otherwise, the non-parametric Mann Whitney U test was applied. Chi-squared test or Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables with odds ratio were presented where applicable. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation was used to present the linear relationship between 2 quantitative variables. One Sample T-test or Wilcoxon Signed rank test was used to assess the SF-36 domains of the subjects subgrouped by gender with the norm in Singapore. Finally, a linear regression was performed to determine significant predictors on the quality of life outcomes and a logistic regression for severe BES or BDI. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Group Characteristics

In the 1-year study period, a total of 184 patients aged between 21 and 65 years old were enrolled in the weight management programme. Eighty-two patients agreed to complete the 3 questionnaires. Participants were significantly younger than non-participants (P = 0.001) and females were less likely to participate (P = 0.018). The 2 groups did not differ otherwise.

Of the 82 participants, 53.7% (n = 44) were female and the remaining 46.3% (n = 38) were male. Their age ranged from 21.7 to 64.3 years old, with a mean age of 40.2 years and a median age of 40.2 years. The ethnic group was 65.9% (n = 54) Chinese, 22% (n = 18) Malay, 11% (n = 9) Indian and 1.2% (n = 1) classifie0d as “Others”.

The BMI from this group ranged from 23.2 to 61.9 kg/m2. The mean and median BMI were 33.3 kg/m2 and 32.3 kg/m2, respectively. The overweight and obese patients comprised 51.3% of the group and the severely and morbidly obese patients comprised 48.7% of the group.

Comorbid medical conditions were common. Of all the participants, 65.9% had at least 1 chronic medical condition. Orthopaedic problems were the most common (36.6%),

followed by vascular risk factors such as hypertension (26.8%) and raised serum lipids (23.2%).

Comorbid or past history of psychiatric conditions were rare in the study group. Only 4 participants (4.9%) reported a history of psychiatric disorder – 1 with anxiety disorder and 3 with mood disorder. None of them were on treatment or follow-up at the point of entering the study.

Psychological Scales

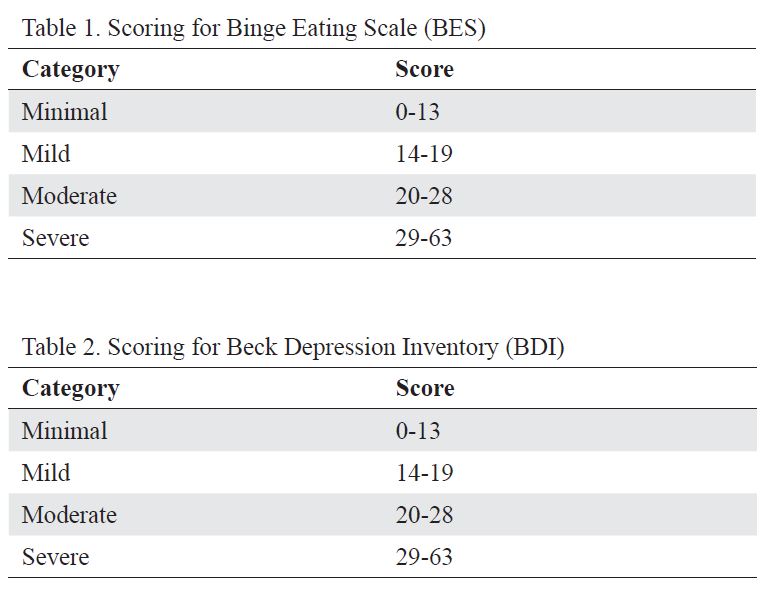

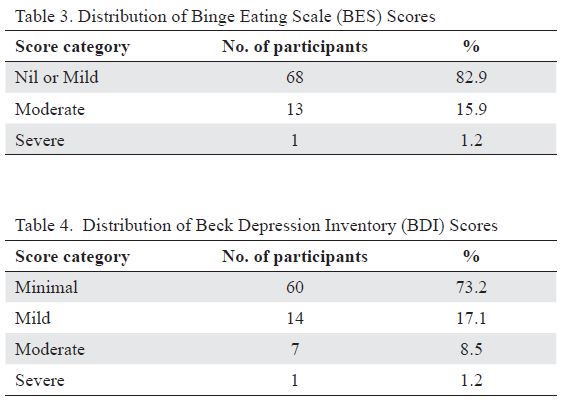

Scores on the Binge Eating Scale (BES) for the group ranged from 0 to 33 and the distribution of scores is shown in Table 3. The mean (±standard deviation) score was 10.73 (±6.8) and the median score for the group was 10.0.

Moderate and severe symptoms were found in 17.1% of the group and these patients were significantly more likely, compared to those with no or mild symptoms, to have a past history of psychiatric condition [Odds ratio (OR), 18.3; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.7-191.8].

The distribution of scores on the BDI is shown in Table 4. The scores ranged from 0 to 30, with a median score of 7.0 and a mean score of 9 with standard deviation of 7.25.

In this group, 9.7% of them who had moderate to severe depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to have severe and morbid obesity [OR, 8.7; 95% CI, 1.02-74.3].

On multivariate analysis, none of the demographic variables or clinical history variables were significantly predictive of more severe BES or BDI scores. More severe BES scores (moderate and severe range) were not predictive of more severe BDI scores (moderate and severe range) [OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 0.72-16.5]. However, a relationship between binge eating and depression was supported by the positive correlation between the absolute scores on the 2 scales (r = 0.459; P <0.01).

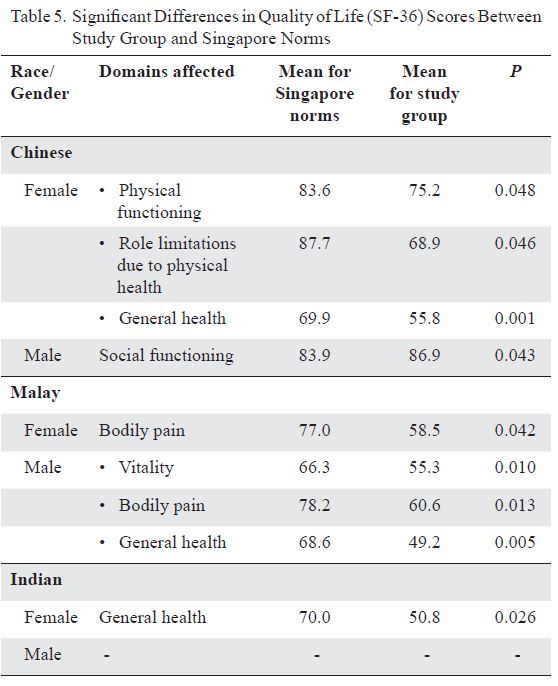

Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-36) Scores SF-36 scores for the participants were collated and compared to the norms in Singapore, which are classifi ed by gender and race. Overall, the different subgroups showed impairments in various domains. Only Indian males showed no impairments compared to their population norms. In general, the domains affected were related to physical health.

The significant differences between the participant groups and local norms are summarised in Table 5.

None of the demographic variables – age, gender, race and severity of obesity – were associated with significant deficits on quality of life scores in any domain. When adjusted for the other variables, the severity of binge eating was found to impact only the domain of role limitation due to emotional problems (P = 0.024).

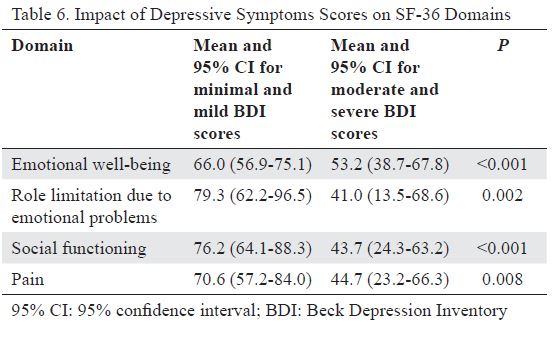

The severity of depressive symptoms was found to impact on multiple domains of the SF-36 –that is (i) emotional well-being, (ii) role limitations due to emotional problems, (iii) social functioning and (iv) pain. A summary of the significant effects are shown in Table 6.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

Data was retrospectively collected from medical records of all new adolescent outpatients referred for psychiatric treatment (ages 13–19) seen at the Psychological Medicine Centre of Changi General Hospital, Singapore, from 2013 to 2015. All data was de-identified and study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at Changi General Hospital. Each patient’s demographic data (e.g., age, gender, employment, living arrangements and parental marital status) and clinical information (e.g., presence and type of DSH behaviours, primary diagnosis, past abuse, alcohol use, smoking behaviour, family history of psychiatric illness and forensic history) were obtained from routine psychiatric intake interview records. In order to avoid unintentionally assessing treatment effects on DSH behaviours, only data from the intake interview was used. In this study, DSH was defined as the intentional self-inflicted destruction of bodily tissue, without the intention to die and excluding culturally sanctioned procedures. Primary diagnoses were made according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19.0. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic and clinical variables. Pearson’s Chi square tests were used to analyze the relations between DSH and categorical variables. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Candidate risk factors were screened using univariate logistic regression and variables with a value of p < 0.2 were further analysed using multivariate stepwise logistic regression where variables were entered sequentially into the model, and the model with the best fit controlling for confounding variables was selected.

Results

The final sample consisted of 398 adolescents (mean age = 17.5 ± 1.4 years) of whom 203 (51%) were males. Majority of the sample were students (n = 316, 79.4%) who lived with both biological parents (n = 299, 75.1%) and had married parents (n = 309, 77.6%). The most common primary diagnosis was depressive disorders (n = 106, 26.6%), followed by adjustment disorders (n = 104, 26.1%) and anxiety disorders (n = 96, 24.1%). 98 adolescents (24.6%) had at least one first degree relative with a psychiatric disorder. About one-fifth of the sample reported current or past history of smoking behaviour (n = 77, 19.3%) and alcohol use (n = 89, 22.4%). Selected demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample can be found in Table 1. 23.1% (n = 92) of the sample engaged in at least one type of DSH. The most common type of DSH reported was cutting (n = 78), followed by hitting or punching (n = 8), scratching (n = 1) and multiple methods (n = 5; see Table 1). Females were significantly (about threefold) more likely than males to engage in DSH, 𝜒2 (1, n = 393) = 28.3, p = 0.00, 𝜑 = 0.274. More females (n = 63) compared to males engaged in cutting (n = 15). Those who engaged in hitting or punching were all males (n = 8). Among adolescents with DSH, 73.9% were female, 44.6% had a depressive disorder as their primary diagnosis, 41.3% had a current or past history of alcohol use, 33.7% had a current or past history of smoking, and 32.6% had a positive family history of psychiatric illness. Most patients with DSH lived with their biological parents (71.7%) and 12% had a past or current history of physical or sexual abuse. Table 2 compares the risk factors of adolescents presenting with and without DSH. DSH was found to be significantly associated with female gender, depressive disorders, alcohol use, smoking and past abuse. These five variables were then further analyzed using stepwise logistic regression, where variables were entered sequentially into the model, and Table 3 illustrates the model with the best fit controlling for confounding variables. DSH was significantly associated with female gender (odds ratio [OR] 5.03), depressive disorders (OR 2.45), alcohol use (OR 3.49) and forensic history (OR 3.66), but not with smoking behaviour, living arrangements, parental marital status, family history of psychiatric illness or history of abuse (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

DSH is harmful to the body and can result in unintentional death. Adolescents who engage in DSH represent a vulnerable and high-risk population. The main goal of this study was to examine the prevalence, nature and associated risk factors of DSH among Singaporean adolescents in an outpatient setting. This will improve our understanding of the population attending psychiatric services for young people, identify at-risk groups for DSH and design targeted interventions for DSH and its associated risk factors.

The prevalence of DSH in this study (23.1%) was similar to an earlier study in Singapore. The consistency in this finding, in addition to the sizeable number of patients involved and the equal gender proportion in the current sample, contributes to the accuracy in estimating prevalence. Given that DSH can sometimes be a secretive act, the consistency in prevalence across time suggests that DSH continues to be a significant feature of adolescents presenting with psychiatric symptoms.

The prevalence of DSH in this study was lower than that generally reported in Western clinical samples, although there were similarities in the nature of presentation and some associated factors. This may be unsurprising given the growing impact of the internet on globalization and exposure to Western media, which may facilitate the gradual homogenizing of how mental illnesses and coping behaviours such as DSH manifest worldwide.

Consistent with previous research on gender differences in DSH in both Western and Asian studies, female adolescents in this study were about three times more likely to engage in DSH than males. These gender patterns have been suggested to reflect the higher rates of depression and anxiety in females as well as the differential ways in which males and females respond to emotional distress. Males have been known to have a greater risk-taking propensity and tend to engage in more externalizing coping methods,

whereas females tend to engage in more internalizing coping methods. Findings also mirror prior research on the associations between DSH and depression, alcohol use and delinquent behaviours. Alcohol use and delinquent behaviours may be associated with disinhibition and recklessness, which may lead to increased DSH. Heavy alcohol use and depression have also been significantly associated with DSH among Hong Kong adolescents and it has been suggested that alcohol use may independently increase DSH, or depression may drive adolescents to self-medicate using alcohol. Although DSH was positively associated with a forensic history in this study, more research on this association is needed as the number in this study was small; only 8 patients with DSH had a forensic history.

DSH was not significantly associated with poor family structure (i.e., not living with both biological parents and not having married parents), positive family history of psychiatric disorder and history of abuse, despite these factors being commonly associated with depression and DSH. However, because the current sample was comprised mostly of adolescents who were in school, not smoking, living with both biological parents who were married, had no positive family history of psychiatric disorder, and had no history of drug use and physical or sexual abuse, it is possible that DSH, as a symptom, may be associated with different risk factors when investigated within different socio-demographic profiles. Singaporean adolescents who engaged in DSH have been found to have higher perceived invalidating home environment, despite being from intact families [27]. This finding suggests the need for further research on how the quality of family relationships, rather than the type of family structure, may be implicated in the development of DSH in Singaporean adolescents. Further, the lack of association between DSH and a positive family history of psychiatric disorder may also be attributed to the lack of accurate report from the adolescent patient. Because of the stigma and common misperceptions towards mental illness in Singapore, many individuals cope by withholding information to avoid discrimination; this may mask the presence of mental illness in some families. Future studies would benefit from the use of more sensitive indicators to investigate DSH and its associations with social and familial stressors and supports.

The positive associations between DSH and female gender, depressive disorders, alcohol use and delinquent behaviours suggest that it may be helpful to refine interventions in order to target these factors. For example, developing group therapy programs tailored for adolescent females, including formal screening tools for depressive disorders in patients presenting with DSH as well as addressing alcohol use and delinquent behaviours which may at times be overlooked during discussions about DSH. Because under-aged alcohol use and delinquent behaviours are often socially influenced, consistent social supports provided via individual and family psychoeducational, case management, psychotherapy groups and a supportive familial environment are important in managing these behaviours.

Several limitations warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal conclusions. Future prospective longitudinal studies with data on DSH among Singaporean adolescents are needed. Further, because data from this study were drawn from specialist outpatient clinics, the generalizability of our findings to community or primary care settings may be limited.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds to our understanding of the phenomenon of DSH behaviours among Singaporean adolescents. Continued research is needed to expand our understanding of DSH and its associated risk factors and to refine interventions to include the most feasible, culturally-sensitive and cost-effective treatment targets on group and individual levels. In particular, clinicians should not only aim to analyze and modify the antecedents or circumstance around which DSH occurs for the adolescent, but also look to minimize associated risk factors such as low mood, alcohol intake and delinquent behaviours. Furthermore, DSH has been increasingly described within the scientific literature since the 1970s, it would be interesting to see whether and how changes in the affected population and associated factors over time may impact on the meanings, motivations and manifestation of DSH presenting in adolescents.

REFERENCES

1. Pattison EM, Kahan J. The deliberate self-harm syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(7):867–72.

2. Nock MK. Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–63.

3. Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-harm: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:226–39.

4. Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp JJ, Lewis SP, Walsh B. Non-suicidal self-injury. Cambridge: Hogrefe Publishing; 2011.

5. Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiat Ment Health. 2012;6(1):10.

6. Brunner R, Kaess M, Parzer P, Fischer G, Carli V, Hoven CW, et al. Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behaviour: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:337–48.

7. Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Lisa L, Sim L. Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. J Abnorm Psych. 2011;39:389–400.

8. Skegg K. Self-harm. Lancet. 2005;366:1471–83.

9. Jacobson CM, Muehlenkamp JJ, Miller AL, Turner JB. Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:363–75.

10. Lewis SP, Heath NL. Non-suicidal self-injury among youth. J Pediatr. 2015;3(166):526 30. 11. Nock M, Joiner TE, Gorden KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144:65–72.

12. Kidger J, Heron J, Lewis G, Evans J, Gunnell D. Adolescent self-harm and suicidal thoughts in the ALSPAC cohort: a self-report survey in England. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:69.

13. Asbridge M, Azagba S, Langille DB, Rasic D. Elevated depressive symptoms and adolescent injury: examining associations by injury frequency, injury type, and gender. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):190.

14. Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, de Wilde EJ, Corcoran P, Fekete S, van Heeringen K, De Leo D, Ystgaard M. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: comparative findings from the Child and Adolescent Self-Harm in Europe (CASE) study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):667–77.

15. O’Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Miles J, Hawton K. Self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in Scotland. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:68–72.

16. Plener PL, Libal G, Keller F, Fegert JM, Muehlenkamp JJ. An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1549–58.

17. Giletta M, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Ciairano S, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: a cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:66–72.

18. Loh C, Teo YW, Lim L. Deliberate self-harm in adolescent psychiatric outpatients in Singapore: prevalence and associated risk factors. Singapore Med J. 2013;54(9):491–5.

19. Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. An investigation of differences between self-injurious behaviour and suicide attempts in a sample of adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(1):12–23.

20. Lloyd-Richardson EE, Perrine N, Dierker L, Kelley ML. Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1183 92.

21. Hilt LM, Nock MK, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal study of non-suicidal self-injury among young adolescents: rates, correlates, and preliminary test of an interpersonal model. J Early Adolesc. 2008;28:455–69.

22. Watanabe N, Nishida A, Shimodera S, Inoue K, Oshima N, Sasaki T, et al. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents aged 12–18: a cross-sectional survey of 18,104 students. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2012;42(5):550–60. 23. Shek DTL, Lu Y. Self-harm and suicidal behaviours in Hong Kong adolescents: prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Sci World J. 2012;2012:1–14.

24. Cheung YT, Wong PW, Lee AM, Lam TH, Fan YS, Yip PS. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behaviours: prevalence, co-occurrence and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 2012;48:1133–44.

25. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

26. Watters E. Crazy like us: the globalization of the American psyche. New York: Free Press; 2010.

27. Tan A, Rehfuss M, Suarez E, Parks-Savage A. Nonsuicidal self-injury in an adolescent population in Singapore. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;19(1):58–76.

28. Lim L, Goh J, Chan YH. Stigma and non-disclosure in psychiatric patients from a Southeast Asian hospital. Open J Psychiatry. 2018;8:80–90.