Understanding adolescent depression in Singapore:

a qualitative study

Ngar Yee Poon, MMed (Psych), MRCPsych, Cheryl Bee‑Lock Loh, MMed (Psych), MSc (Child & Adolesc Mental Health)

1Department of Psychological Medicine, KK Women’s and Children Hospital, 2Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Introduction: This qualitative study aimed to understand the lived experiences of adolescents with depression seeking help in our healthcare system, with the focus on initial symptoms, experience of care and reflection after recovery.

Methods: Semi‑structured interviews were conducted with 14 adolescents, aged between 13 and 19 years, who were diagnosed and treated for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition major depressive disorder and clinically judged to have recovered at the time of recruitment. Data were analysed qualitatively using thematic analysis, with a focus on how the adolescents spoke about their experience of depression.

Results: The findings suggested that our adolescent participants had initially tried managing depression within their own circle, and that thoughts of suicide and self‑harm, as well as anhedonia–avolition symptoms were the most challenging to deal with. Recovered participants were observed to express a high degree of empathy towards others going through depression.

Conclusion: This study is the first to have surveyed adolescents in our Asian city‑state on multiple aspects of their experience of depression. It allows a wide‑ranging description of this condition and has the potential to improve understanding and inform care delivery.

INTRODUCTION

More than most physical illnesses, the experiences of psychiatric conditions such as depression are affected by the psychosocial world of the patient. This appears to be particularly true when the patient is an adolescent, often living with parents, dependent on family for guidance and provision, facing the pressures of their own particular social milieu and affected by family attitudes to mental health.

All these factors suggest that for clinicians working with depressed adolescents, understanding their particular experience of this condition is an important part of developing a therapeutic alliance and discussing treatment and service planning.

Several recent studies have undertaken qualitative research of clinically similar but culturally different groups. One study in a group of currently or previously depressed African American adolescents and young adults found that the themes coalesced around how the adolescents saw their depression in the context of their interactions with others, emphasising the importance of the social context the patient comes from. One theme emerging from this study, which was less prominent in other studies, was participants experiencing their depression as anger and noticing their own verbal and physical outbursts at those around them. These outbursts resulted from different internal experiences — some found their own behaviour inexplicable, some intentionally provoked fights to gain a sense of relief, and some were unaware that their behaviour was considered mean. In this way, the qualitative interview allowed a greater and more varied understanding of behaviour, in this case, anger, which may otherwise be classified as similar by quantitative methods or external observation.

A qualitative study of depression in American Latina female adolescents found similarities in that each step of the experience of depression and its treatment could be described in terms of social interactions with family, peer groups and mainstream authority figures. A prominent finding that emerged was the ways in which participants described wanting to manage the problem themselves and by not wanting to burden their parents, many of whom were immigrants who were working hard to provide for the family. They also did not talk about their mood problems directly and did not engage consistently with health services when identified. This study would suggest that services designed for Latina adolescents would be more acceptable if they included a high degree of patient autonomy and supported their desire for self‑management.

In a population of depressed adolescents from London, 50% of whom were white British, a brief qualitative interview as part of a larger therapeutic trial reflected a wide range of internalising and externalising symptoms. Participants also emphasised the effect of depression, speaking of having “a bleak view of everything”, “isolation and cutting off from the world” and, from a practical aspect, the difficulties they had in school. The answers and the researchers’ observations showed that the participants were extremely articulate about their inner experiences.

This contrasted with a study conducted among Arab adolescents in Jordanian schools, where researchers decided that carefully chosen, single‑gender, focus groups would increase

participation as opposed to individual interviews. They found that many participants had difficulty describing their inner experiences and were unsure about what “depression” meant as a term. There was a general belief that depression resulted from a lack of faith, although other factors, like negative life events, were also considered. Unlike the other studies quoted here, more traditional explanations were also brought up, like being exposed to envy, being possessed by Jinn and not abiding by family wishes. Fear of labelling was quite prominent among these participants, and most of them said that despite viewing individual psychotherapy favourably, they would avoid such treatments for fear of being labelled crazy. Internet‑based treatments were seen as appealing for the anonymity they would provide. This study highlights the cultural milieu of depressed adolescents in a more conservative society. Although globalisation continues to increase and the Internet provides alternative views, many teenagers invariably have opinions and opportunities shaped by their immediate communities.

Therefore, we undertook this study to understand the lived experiences of adolescents with depression seeking help in our healthcare system, mainly the initial symptoms, their experience of care and their reflections after recovering. This study is unique as we focused on an Asian population with a highly urbanised multi‑ethnic and multicultural society background.

METHODS

Potential participants were recruited from the Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore. Inclusion criteria were patients aged 13–19 years, who were treated for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) major depressive disorder and clinically judged as recovered within the last 3 months at the time of recruitment. The subjects were interviewed after they had recovered from depression, and therefore they could provide a narrative of the entire illness experience, including recovery. This also allows the reader to hear subjects who went through similar situation in their illness journey. Only subjects who had recovered were included in our study, as individuals who are still experiencing depression would find it difficult to fully cooperate with a qualitative interview because depression is associated with psychomotor retardation, poor concentration and lack of drive. All patients were further screened on the day of the interview and had to attain a patient health questionnaire (PHQ) score <11.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parentsor legal guardians, and all patients gave written assent. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from Singapore Health Services Centralised Institutional Review Board. None of the patients received any compensation for participating in this study.

All the interviews were conducted in the hospital’s outpatient clinic by the two authors, who are psychiatrists not directly involved in the care of the patients. Both authors are female and have medical degrees and postgraduate specialist qualifications, including training in qualitative research methodologies.

The interview was semi‑structured in nature with suggested leading questions to explore the areas of interest; further elaboration was elicited until no additional information was obtained, as reflected by the participant or judged by the interviewer. The leading questions are detailed in the Supplemental Digital Appendix. The three broad categories of questions were:

1. Participants’ journey towards seeking professional help for depression: what they understood of the condition before they were affected, the most difficult symptoms they experienced, how they coped with the first symptoms, and the attitudes they encountered when seeking professional help.

2. Experiences after diagnosis: attitudes towards the diagnosis, and their experiences with taking medication and undergoing psychotherapy.

3. Their reflections when looking back on their depressive episode.

The participant were interviewed alone and only once, and the sessions were recorded and transcribed thereafter. The transcripts were checked for accuracy by the study team. The participants did not review the transcripts.

The transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis. Each author independently read the transcripts in their entirety with the aim to familiarise themselves with the context of individual answers given. Each author independently noted initial ideas gathered from the transcripts and organised them under broad descriptive groups. They then shared their findings to look for common groups and resolved any discrepant findings through discussion. Thereafter, the authors identified patterns between the broader descriptive groups and grouped similar ones together. This process was repeated several times, merging overlapping ideas and creating new ones, until all significant points could be placed into distinct groups. The authors noted that themes elicited for the main headings, namely experience of depressive symptoms, reaction to receiving a diagnosis and concerns about relapse, were represented by a majority of the participants. With the achieved sample size of 14, the authors judged that no further subjects needed to be recruited.

RESULTS

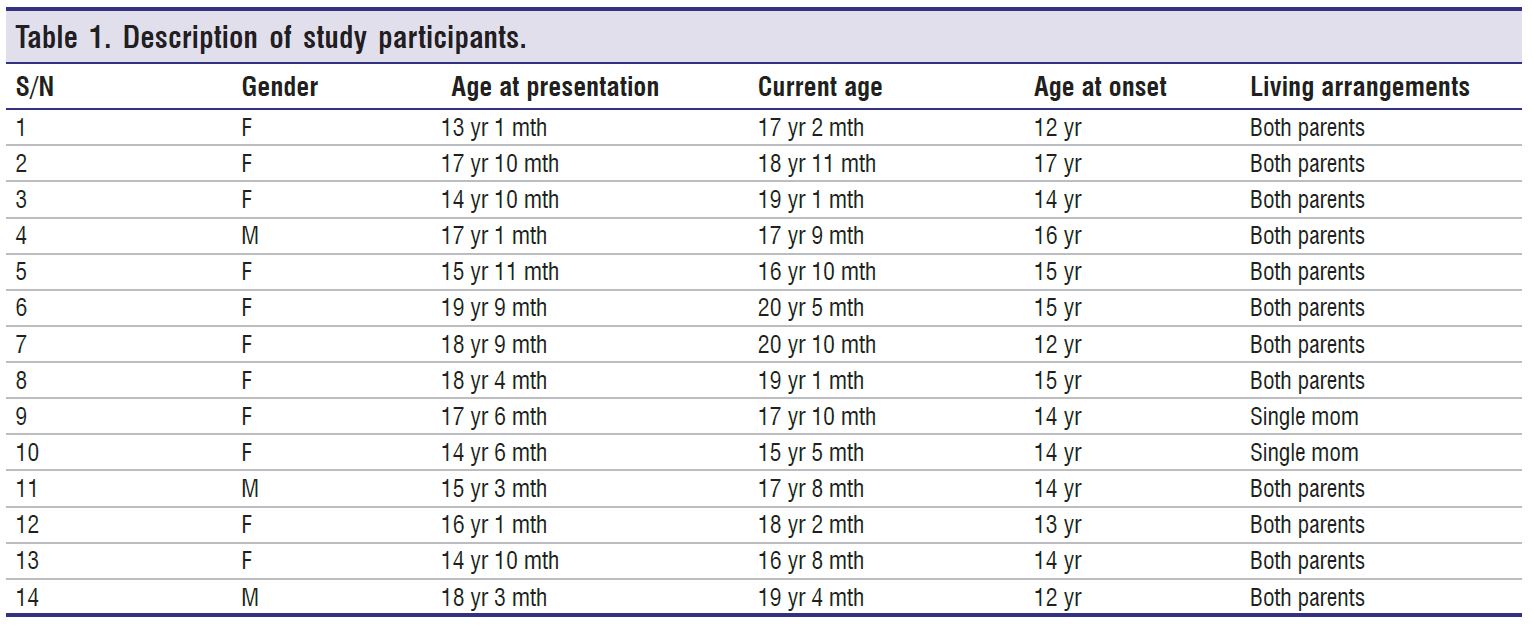

A total of 14 adolescents (11 female, three male) were recruited. The age at presentation to our service ranged from 16 years and 8 months to 18 years and 3 months. The age at onset of symptoms ranged from 12 to 17 years. All were students at the time of the interview. Clinical and demographic data are displayed in Table 1. Out of the 14 participants, 11 (79%) had a history of deliberate self-harm (DSH) and six (43%) had a history of suicide attempts. All of them attempted suicide by overdosing on medication and one had attempted hanging. Four (29%) participants have had a psychiatric hospitalisation. All but one (93%) participant had been treated with medication, and all had received psychotherapy. The length of each interview ranged from 23 to 88 min, with a median duration of 49 min.

Knowledge of depression before diagnosis

In this study, seven (50%) participants expressed that before they experienced depression themselves, their knowledge of it was limited. Their responses ranged from knowing absolutely nothing to not have any reason to find out more about it. One shared that she never thought it would happen to her. Another observed that the term depression was often loosely used among teenagers, saying “Among youth, little things, we just say oh, feeling depressed”.

Regarding sources of information on depression, five (36%) participants reported learning about adolescent depression via television portrayals and online sites or forums, and another five (36%) learnt about the signs and symptoms from observing and interacting with friends who had been diagnosed with depression. None of the participants reported input from parents, other significant adults or educational material from school.

Stresses associated with the onset of depression

Regarding possible stresses contributing to the onset of depression, most of them identified problems in the areas that form a large part of routine adolescent life — school demands, peer relationships and family life.

Eight (57%) participants reported school demands as a stressor. Not being able to meet academic demands resulted in negative experiences, which included feeling down when comparing themselves unfavourably to others and receiving negative comments from teachers. Three (21%) other participants had a difficult time with peer interactions at school, including bullying, name‑calling, unkind rumours and difficulty adapting to a new school. Six (43%) participants reported problematic peer relationships as stresses — three (21%) described individual conflicts with friends as a trigger for depressed mood, although other situations, such as feelings of betrayal by a group of friends or a lack of emotional support from friends, may also contribute to their depression.

Nine (64%) participants experienced difficulties in family life. Three (21%) described their parents as strict and critical, placing expectations on their children to perform better in

their studies. Seven (49%) participants described challenging family situations, ranging from constant quarrels between the parents, divorce and its impact on them, loss of a parent to feeling neglected by parents who were too busy with work.

Five (36%) participants encountered more unique stressful situations. This included one participant who struggled with being transgender and was uncomfortable with the physical changes of puberty and another who have had chronic back pain that prevented her from pursuing her passion in sports. One participant described feeling guilty about failing to resuscitate a man with a heart attack.

Six participants (43%) felt that there had not been any major significant event that triggered their depressed mood. Even though some life stresses were present, they reflected that depression resulted from a build‑up of multiple small problems, coupled with their inability to cope and personality, as well as the reactions and behaviours of those around them.

Personality factors discussed included being sensitive, easily hurt by criticism and a tendency to be influenced by low mood in others. They thought that these traits often resulted in repeated episodes of feeling down, which seemed to accumulate over time and contribute to the major mood episode. Perfectionism and setting high standards for oneself, which often led to feeling demoralised when goals were not achieved, were also reported.

Prominent symptoms

When asked to describe the most distressing or most prominent symptom of depression they had experienced, 13 of the 14 participants (93%) reported either one of these two symptom groups: suicidal/self‑harm thoughts or anhedonia/avolition.

Nine (64%) participants struggled with suicidal and self‑harm thoughts. A big driver of suicidal thought was feelings of guilt. One participant expressed it as: “I felt I was a huge burden to parents and friends” and “better off not being here”. Another said, “I feel useless and lots of self‑hate”. One said that she thought of suicide because of her guilt feelings, but that she also felt that others would judge any suicidal act as being “attention‑seeking”. She did not want this reputation, and being unable to clearly resolve these thoughts and feelings made her mood even worse.

The suicidal thoughts were experienced as intrusive and unwanted. Many actively struggled to stop them, but described these attempts as futile. A participant said, “No matter how hard I tried, it would still occur”. Even though the overwhelming nature made many want to act on them, there was a sense that these were not normal thoughts. “It was the only thing I wanted, though previously it made no sense”, said a participant. Participants were often able to distinguish between suicidal and self‑harm thoughts. Self‑harm thoughts were often described in conjunction with suicidal thoughts, but had functions such as “to feel real”, “as an outlet for negative thoughts”, “to punish myself” and “to get help”.

The nine (64%) participants with prominent anhedonia/avolition symptoms described having no interest in anything and not wanting to interact with anyone. This prevented them from participating in activities, including attending school, meeting up with friends and exercising. One described the experience as “feeling each second go by and feeling completely blank”. Being in this state had many adverse effects, and looking back, the participants were able to see the problems it created. It led to conflicts with people who did not understand their behaviour.

“Parents upset and were screaming, and I scream back”, said a participant. It resulted in a poor academic performance, which added to the sense of failure and guilt. The inability to get on with normal life also had the quality of missing out and hopelessness. “Everyone is going on with life, I am just stuck …. I am going to be alone forever”, said a participant.

Self-coping before seeking professional help

Self‑harm was identified not only as a distressing symptom, but also as a means of coping with depressive symptoms in general. It seemed to be part of a vicious cycle of feeling down

and self‑harming to address the distress while experiencing self‑harm as unwanted in itself. Seven (50%) participants viewed it as an alternative and more manageable form of pain compared to the emotional pain of depression. One participant said, “Heart pain very uncomfortable … transfer to physical pain that can be controlled”.

Talking to friends for support was reported by nine (64%) participants. Participants reported that their friends were their main confidantes, as they felt that their friends could be trusted.

With friends, they also felt understood and less pressure to behave or speak in a certain way. Five (36%) participants felt it was because friends understood that they just wanted to have someone to talk to and they made fewer demands about changing behaviour or acting on suggestions. One participant made a less‑common observation that, although she enjoyed and needed her friends, she realised that sometimes her mood problems were beyond what they could offer as teenagers themselves: “We were at the age where we can’t really empathise with people…. They were my lifeline but unstable”.

Nine (64%) participants reported changing some aspects of their social and personal activities to see if that would help. These included sleeping more to stop thinking about problems, hanging out with friends as a way to entertain themselves, drinking alcohol to aid sleep, and spending more time on computer gaming, social media and music. Although these are common modes of entertainment for adolescents, they were described by participants as being used to pass time, find material that resonated with their mood and learn more about their own depression.

The option of talking to adult family members was brought up in many interviews, and five (36%) participants reported telling family members, most commonly parents. All said they turned to their parents as a means of accessing professional help because they were getting worse and their own attempts at solving the problems were not helping. Many received professional help as a result of parents’ involvement, but this was not without problems. One observed, “They (parents) were frustrated and don’t know how to help, end up saying hurtful things”. Five (36%) participants held back from sharing with their parents and preferred to cope without them. Four of them said that their parents did not believe in the existence of mental illness and would not understand depression. One participant said his parents did not think he had depression when it was tentatively brought up, and one participant said that she had never confided in her father about anything, as he was abusive.

Three (21%) participants described a sense of helplessness and hopelessness when depressed, such that they felt nothing would work and there was no point in trying anything.

Attitudes towards psychiatry

When asked about their attitudes towards psychiatric care when it was first proposed, six (43%) participants reported being quite keen to see a psychiatrist, as they believed it would be helpful and three (21%) felt that their condition was so severe that they had no other option. They conveyed a sense that seeing a psychiatrist was a last resort, with statements such as, “I cannot deny the problem anymore” and “something has to be done”. Five (36%) participants had reservations about seeing a psychiatrist, due to a negative opinion of psychiatrists, which led to anxiety. Some reasons for their reservations included a belief that psychiatrists see only crazy people, or a feeling that they are unable to open up to unfamiliar adults or that psychiatrists would expect a lot from them. One patient said she thought she would have to “get onto their level and must speak good English”. Two participants (14%) brought up concerns that they would be viewed negatively by others if it was known that they had seen a psychiatrist.

Participants also reported on the attitudes of their families when they were made aware of the need to consult a psychiatrist. Seven (50%) participants felt that their family was supportive (e.g., “If this is going to help, we should just go for it”). They also felt that their family was more understanding after they realised there was a problem.

Five (36%) participants received an overtly negative response, with family members disapproving of the decision to consult a psychiatrist and expressing that what the patient suffered was not depression or not severe enough to warrant psychiatric intervention. Instead, some family members attributed the problem to normal behaviour during puberty, a young person’s lifestyle choices, or a young person being too “dramatic” about personal problems or trying to use depression as an excuse for not fulfilling expectations at home and in school.

Reaction to diagnosis of depression

The participants’ reaction to receiving a diagnosis of depression from the psychiatrist clustered around three main themes: relief and reassurance; hopefulness; and being too depressed to react in any other way.

Eight (57%) participants described feeling relieved or reassured, as a formal diagnosis from a professional meant that what they were experiencing was a real illness, and not a personal flaw or a product of their imagination. Five participants (36%) talked about feeling more hopeful, as the formal diagnosis provided them with a path to improvement. This group of participants felt that the diagnosis would enable them to receive proper professional treatment, and that professionals would help their parents to understand their condition better.

Five (36%) participants had reactions that were symptomatic of their depressed state, such as feeling emotionless, too tired to care, hopeless (being given the label of depression would not help), guilty (they did not feel they deserve a diagnosis or treatment) and abnormal in some way. One participant said, “So deep into depression that I felt nothing”

Views on taking medication

A minority (29%) of participants and their family members were in favour of taking medication. This group believed that medication was necessary and were willing to try it. “Just like mother taking hypertensive medication to control her blood pressure”, commented a participant.

In half of the participants, only one party (either the participant or the parents) was in favour of medication use. The reasons for parents’ disapproval included rejection of the diagnosis of depression, the stigma of having their child on psychiatric treatment, and fear that their child would need medication indefinitely once they were started on it. Two (14%) participants who had initially refused medication described various fears and negative perceptions, including fear of unacceptable side effects such as weight gain, disliking the hassle of daily medication, and not believing that medication could help with low mood. Both of the participants eventually received a combination of medication and psychotherapy.

Views on therapy

Various positive experiences with psychotherapy were reported. Six (43%) participants reported that just having somebody to talk about their problems with was the most helpful thing about psychotherapy. Five (36%) participants appreciated having an adult provide an alternative and more positive point of view to their problems, and eight (57%) of them described having gained some knowledge during the session, either about real‑life

problem‑solving or relaxation techniques. Three (21%) participants described enjoying the sessions because of the therapist’s attributes. They described meeting therapists who were friendly and non‑judgemental about the problems shared, and one participant shared that she liked it when the therapist related personal stories in the session.

We further explored the related topic of sharing personal problems with a therapist who is a virtual stranger. Five (36%) of them said they preferred this, as they would worry less about being judged or the person having negative preconceived notions about them. Four (29%) of them said that it took some time to warm up, but they were more willing to share once they realised how helpful therapy was. Two (14%) participants said they thought of the therapist as a professional, someone who would give more competent advice, and that being an unfamiliar person was not a consideration at all.

Mirroring this, the reasons five other (36%) participants gave for not finding therapy helpful were related to meeting therapists they did not enjoy talking to. They relayed that the therapists were repetitive in their advice even when they

were not improving, and this was felt to be frustrating and annoying. Three (21%) of them were not comfortable in the process of therapy, as they did not want to talk about personal matters with someone unfamiliar and found it unpleasant when talking led to being emotional. Two (14%) participants were not convinced about the therapeutic process, and expressed that their depression was biological or had its roots in family problems and so a therapist could not help.

Looking back

All participants were asked to reflect on their experience with depression and share what they felt had been helpful in their recovery. Seven (36%) participants mentioned support from family or friends as instrumental. They described people who acknowledged their illness, prioritised their recovery and influenced them with positive attitudes. They also described these people as performing small but thoughtful acts such as keeping in touch when they had dropped out of school.

Changes in themselves and their external environment were mentioned as a factor by five (36%) participants. They described changes such as developing a different attitude to the problem, better pain control for a physical condition and lessened academic demands as positive changes.

Eleven (79%) participants felt that the treatment for depression was an important factor. They noticed the difference in themselves when they were on medication, and they felt that therapy had taught them better ways to deal with their problems and thus improved their mood.

What they would have done differently?

Participants commented mostly on how they had communicated their problems in the initial phase of their depression. Five (36%) participants said they would be more open about sharing their problems with others, including professionals. They felt that therapy would have been more effective if they had been more open. Fears about the response to their sharing held them back — from fear of hospitalisation if the extent of their problem was known to fear of being a burden to others. Two (14%) of them felt that they should have been more selective with whom they shared their problems with. They regretted sharing with people who labelled them as attention‑seekers, who were not able to keep confidentiality, or who were themselves depressed and made the participants feel more down.

Four (29%) participants said simply that they would have sought help earlier, but again fears about the response to requests for help, such as fear of not being believed, held them back.

Five (36%) participants felt they should have used different coping strategies when they were depressed. They later realised there were more helpful strategies such as listening to calming music, drawing as a distraction, finding inspirational quotes and celebrating small goals, instead of methods such as alcohol use or self‑harm.

Worries about relapse

We explored with these young participants their worries about having a relapse at some point in the future after having recovered from their depression. Relapse was a worry at least some of the time for 11 (79%) participants, while one said she worried all the time and the rest did not worry about it at all. Their assessment of risk seemed to be based on having residual symptoms or seeing that there would be life changes ahead that they felt would be potential stresses. Eight (57%) of them expressed a belief that they would be able to cope better in the event of a relapse. This is because they had better coping strategies and understood their emotions better now, and they would seek psychiatric help when the need arises.

Advice for teenagers experiencing depressive symptoms

Seven (50%) participants encouraged other teenagers who are feeling depressed to seek professional help as soon as possible. They wanted to tell others that psychiatric care had been helpful and had given them clarity about the problem. One participant advised, “It is important to have access to a perspective that is not a teenager’s perspective because as much as you might think that you are very mature.… having the objective adult professional perspective is something which is very valuable”.

Expressing their own regrets, seven (50%) participants advised others to acknowledge and share their problems, as sharing is an important form of release. One of them said, “I used to

bottle up a lot and one day, I just exploded and it’s not a nice feeling…. Just like ticking time bomb”. If there was no one to share it with, she suggested young people to “write it in notes

or diary for themselves”. Four (29%) participants recalled their own hopelessness during their depression and wanted to send a message of hope:

“Now may seem very gloomy and dark, but there’s always another side of the rainbow”.

Singapore Medical Journal ¦ Volume XX ¦ Issue XX ¦ Month 2024 7 “You’re only going to be down for a while, and just got to fight through it”.

“You are in this point where you just feel so low and you can’t get out of it, there will always be better moments and you’ll always be able to get out of that even if it feels impossible”.

DISCUSSION

The current study adds to the knowledge of the lived experience of adolescent depression in Singapore. Taken together, a few findings were significant: adolescents managing depression within their own circle, the vicious cycle of depressive symptoms and critical responses, and empathy after the experience.

Many aspects of the participants’ experience of depression were more influenced by their interactions with peers and mass media than by their interactions with adults such as parents and teachers. These included the adolescents’ previous knowledge of depression, their peer relationships as stresses contributing to depression, and finding support in peers before seeking professional help. This finding has implications for how we reach out to depressed adolescents, increase their awareness of depression as an illness and create a supportive network for them. It suggests that general mental health education would be helpful because adolescents tend to get involved with their friends’ mental health problems. These friends may also need support themselves because being overwhelmed by their peers’ problems can be stressors for their own depressive episodes.

Concurrently, this finding highlights the absence of adult involvement in teen depressive episodes until late, when adults were seen as being instrumental in accessing professional help for a problem that had become unmanageable. This is a similar theme to that found in the study of American Latina girls,[2] where it was thought that the parents being busy at work as immigrants trying to provide for their families made the young girls not want to bother them. In a British study,[6] depressed teens elaborated on how they found friends to be a source of enjoyment and distraction when they were depressed, and some may have lacked desired parental support. These diverse populations suggest that there are multiple pathways to this finding. This finding also suggests room for improvement in the interactions between adults and young people, where mental health problems can be discussed and supported early on.

The later involvement of adults as a step to accessing professional help was also found in a meta‑synthesis of qualitative studies of adolescent depression,[7] which suggested that talking to both family and friends was a step towards getting professional help. This paper further suggested that being trustworthy and being knowledgeable were qualities considered important by depressed adolescents when they chose to talk to either group.

The most difficult symptoms reported by the subjects, suicide/ self-harm thoughts and anhedonia/avolition, both illustrated the vicious cycle of depressive symptoms inciting critical responses, which then served as further stress when the depressed teen could least afford to manage it. Suicide and self‑harm may be viewed as manipulative and attention‑seeking

because the actual act is under voluntary control. Being avolitional is often equated with laziness and not making an effort to recover. The subjects’ descriptions clearly showed that they were greatly distressed by these symptoms but felt overwhelmed and unable to control them, and that they were aware of the reasons behind the responses they received but were unable to change any of these misperceptions.

This finding of a vicious cycle at work has been echoed in other qualitative studies. The vicious cycle identified included depressed adolescents withdrawing from others, as a result of avolition and loss of interest,[8] and also because they feared being misunderstood and negatively judged, or to protect others from their negative feelings.[6] Similar to how our participants articulated it, the authors observed that these behaviours worsened the situation by leaving the depressed adolescent unsupported. These findings highlight the importance of education and acceptance of depressive symptoms in the general public, so that difficult behaviour can be understood in the context of an illness and a helpful response can be provided.

Reflections on lived experiences of depression among adolescents are less commonly found in the literature. Many qualitative studies did not touch on this or had participants still in active treatment,[3,6] or a mix of clinical and non‑clinical populations.[4,8] One paper focused on reflecting back on depression and highlighted the helpfulness of talking,[9] as our study population did. Another paper, with patients still not entirely recovered, had adolescents reflecting on the search for ways to understand what they had gone through.[10] It is possible and likely that the mood state of the patient at the time of the interview affects their perspectives.

In our study, the advice of our respondents to other depressed teens — to reach out for help, as there is hope for recovery — reflected an empathy towards the difficulties of being depressed. In this, they reflected a generosity that belies the accusations of being self‑centred and/or manipulative when they self‑harmed or withdrew from activities. We are impressed by the participants’ willingness to share and encourage unknown others who suffer from depression.

The study is not without limitations. This is a small study, which necessarily includes only those who were willing to participate, likely resulting in a group that is more articulate

and less socially anxious. The group also comprised those who had recovered and although they were interviewed not long after recovery, it is possible that aspects of their illness had been forgotten or perceived differently. Interviewing depressed teens in the course of their depression is likely to meet with resistance, but would add a necessary dimension to the understanding of their experiences.

This study opens up numerous directions for future research that were not specifically addressed in this study. This set of interview questions did not specifically lead the participants to comment upon social media use and its effects on their depressive illness. It is interesting to see that it did not spontaneously come up here or in other studies conducted in Western developed nations,[1‑3,7,9,10] while a qualitative study in Nepal mentioned this factor as a prominent cause of depression. We believe there is much scope to explore the nuances of social media’s impact on adolescent depression, as it has become an increasingly normal part of their lives and its demands and pitfalls are accepted as certain normalcy.

In conclusion, this study is the first to have surveyed adolescents in our Asian city‑state on multiple aspects of their experience of depression. It allows a wide‑ranging description of this condition and has the potential to improve understanding and inform care delivery. Our study also provided an opportunity to compare and contrast the experiences of depressed adolescents from different cultural backgrounds to expand our understanding of this common disorder.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content

Appendix at http://links.lww.com/SGMJ/A80

REFERENCES

1. Al‑Khattab H, Oruche U, Perkins D, Draucker C. How African American adolescents manage depression: Being with others. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2016;22:387‑400.

2. McCord Stafford A, Aalsma MC, Bigatti S, Oruche U, Draucker C. Getting a grip on my depression: How latina adolescents experience, self‑manage, and seek treatment for depressive symptoms. Qual Health Res 2019;29:1725‑38.

3. Midgley N, Parkinson S, Holmes J, Stapley E, Eatough V, Target M. Beyond a diagnosis: The experience of depression among clinically‑referred adolescents. J Adolesc. 2015;44:269‑79.

4. Ali Dardas L, Shoqirat N, Abu‑Hassan H, Shanti BF, Al‑Khayat A, Allen DH, et al. Depression in Arab adolescents: A qualitative study. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2019;57:34‑43.

5. Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample size for saturation in qualitative research, a systemic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med 2022;292:1‑10.

6. Weitkamp K, Klein E, Midgley N. The experience of depression: A qualitative study of adolescents with depression entering psychotherapy. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2016;3:2333393616649548. doi: 10.1177/2333393616649548.

7. Dundon E. Adolescent depression: A metasynthesis. J Paediatr Health Care 2006;20:384‑92.

8. Syed SW, Ottman K, Bohara J, Neupane V, Fisher HL, Kieling C, et al. Adolescent perspectives on depression as a disease of loneliness: A qualitative study with youth and other stakeholders in urban Nepal. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health 2022;16:1‑17.

9. McCarthy J, Downes EJ, Sherman CA. Looking back at adolescent depression: A qualitative study. J Mental Health Counselling 2008;30:49‑68.

10. Farmer TJ. The experience of major depression, adolescent perspectives. Iss Mental Health Nurs 2002;23:567‑85.